Next in Google’s Quest for Consumer Dominance–Banking

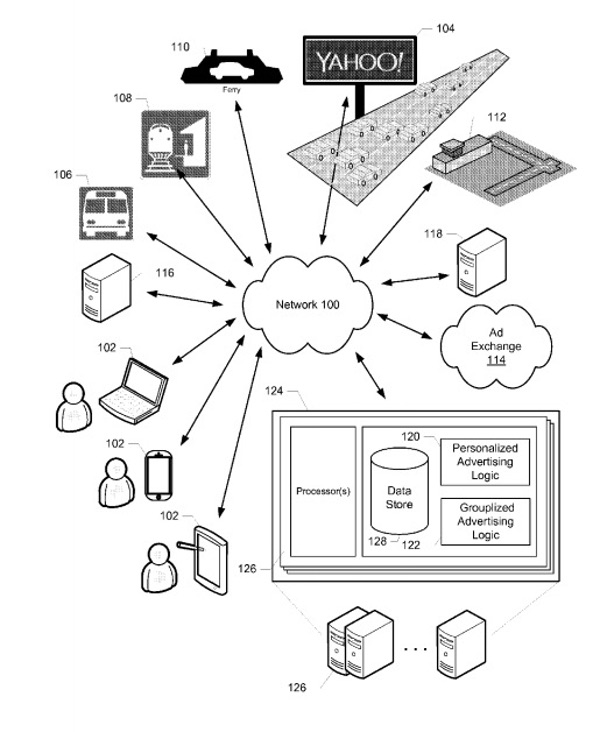

The project, code-named Cache, is expected to launch next year with accounts run by Citigroup and a credit union at Stanford University, a tiny lender in Google’s backyard. Big tech companies see financial services as a way to get closer to users and glean valuable data. Apple introduced a credit card this summer. Amazon.com has talked to banks about offering checking accounts. Facebook is working on a digital currency it hopes will upend global payments. Their ambitions could challenge incumbent financial-services firms, which fear losing their primacy and customers. They are also likely to stoke a reaction in Washington, where regulators are already investigating whether large technology companies have too much clout.

The tie-ups between banking and technology have sometimes been fraught. Apple irked its credit-card partner, Goldman Sachs Group, by running ads that said the card was “designed by Apple, not a bank.” Major financial companies dropped out of Facebook’s crypto project after a regulatory backlash. Google’s approach seems designed to make allies, rather than enemies, in both camps. The financial institutions’ brands, not Google’s, will be front-and-center on the accounts, an executive told The Wall Street Journal. And Google will leave the financial plumbing and compliance to the banks — activities it couldn’t do without a license anyway.

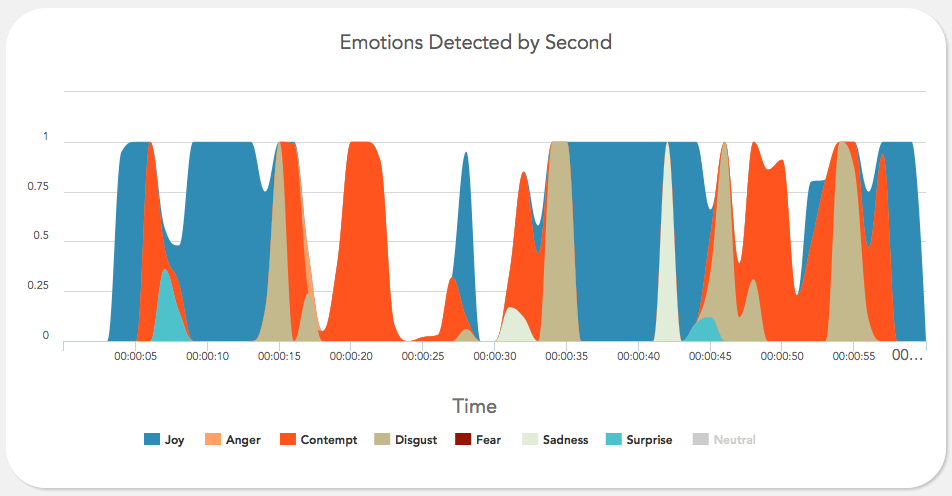

“Right now, in a handful of computing labs scattered across the world, new software is being developed which has the potential to completely change our relationship with technology. Affective computing is about creating technology which recognizes and responds to your emotions. Using webcams, microphones or biometric sensors, the software uses a person’s physical reactions to analyze their emotional state, generating data which can then be used to monitor, mimic or manipulate that person’s emotions.”

“Right now, in a handful of computing labs scattered across the world, new software is being developed which has the potential to completely change our relationship with technology. Affective computing is about creating technology which recognizes and responds to your emotions. Using webcams, microphones or biometric sensors, the software uses a person’s physical reactions to analyze their emotional state, generating data which can then be used to monitor, mimic or manipulate that person’s emotions.”