When is targeted surveillance wrong?

For many of us, that unsettling feeling of being watched is all too real. After all, we live in a world of mass surveillance, from facial recognition to online tracking – governments and tech companies are harvesting intimate information about billions of people. Targeted surveillance is slightly different. It’s the use of technology to spy on specific people.

You may think this is fine, because aren’t people only targeted when they’ve done something wrong? Think again.

From Mexico to the Middle East, governments are wielding a range of sophisticated cyber-tools to unlawfully spy on their critics. A seemingly innocuous missed call, a personalized text message or unknowingly redirected to malicious website for a split second, and without you being aware the spyware is installed.

The people targeted are often journalists, bloggers and activists (including Amnesty’s own staff) voicing inconvenient truths. They may be exposing corrupt deals, demanding electoral reform, or promoting the right to privacy. Their defence of human rights puts them at odds with their governments. Rather than listen, governments prefer to shut them down. And when governments attack the people who are defending our rights, then we’re all at risk.

The authorities use clever cyber-attacks to access users’ phones and computers. Once in, they can find out who their contacts are, their passwords, their social media habits, their texts. They can record conversations. They can find out everything about that person, tap into their network, find out about their work, and destroy it. Since 2017, Amnesty’s own research has uncovered attacks like these in Egypt, India, Morocco, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, UAE, Qatar and Uzbekistan.

Remember, the users we’re talking about are human rights activists, among them journalists, bloggers, poets, teachers and so many others who bravely take a stand for justice, equality and freedom. They take these risks so we don’t have to. But voicing concerns about government conduct and policy makes them unpopular with the authorities. So much so that governments resort to dirty tricks, smearing activists and re-branding them as criminals and terrorists.

Some of the most insidious attacks on human rights defenders have been waged using spyware manufactured by NSO Group. A major player in the shadowy surveillance industry, they specialise in cyber-surveillance tools.

NSO is responsible for Pegasus malware, a powerful programme that can turn on your phone’s microphone and camera without your knowledge. It can also access your emails and texts, track your keystrokes and collect data about you. The worst thing is you don’t have to do anything to trigger it – Pegasus can be installed without you ever knowing.

NSO say they’re creating technology that helps governments fight terrorism and crime. But as early as 2018, when one of our own staff was targeted through WhatsApp, our Security Lab discovered a network of more than 600 suspicious websites owned by NSO that could be used to spy on journalists and activists around the world. We were not wrong. In 2019, thousands of people received scam WhatsApp call, leading WhatsApp to later sue NSO. More recently we documented the cases of Moroccan activists who had been similarly targeted.

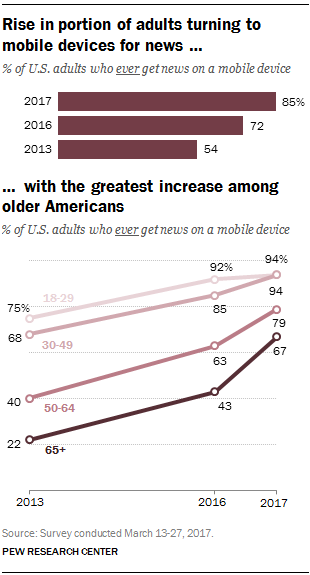

Mobile devices have rapidly become one of the most common ways for Americans to get news, and the sharpest growth in the past year has been among Americans ages 50 and older, according to a

Mobile devices have rapidly become one of the most common ways for Americans to get news, and the sharpest growth in the past year has been among Americans ages 50 and older, according to a