“Influencers” Are Being Paid Big Sums To Pitch Products and Thrash Rivals on Instagram and YouTube

“Influencers” are being paid big sums to pitch products on Instagram and YouTube. If you’re trying to grow a product on social media, you either fork over cash or pay in another way. This is the murky world of influencing, reports Wired. Brands will pay influencers to position products on their desks, behind them, or anywhere else they can subtly appear on screen. Payouts increase if an influencer tags a brand in a post or includes a link, but silent endorsements are often preferred.

Marketers of literature, wellness, fashion, entertainment, and other wares are all hooked on influencers. As brands have warmed to social-media advertising, influencer marketing has grown into a multibillion-dollar industry. Unlike traditional television or print ads, influencers have dedicated niche followings who take their word as gospel.

There’s another plus: Many users don’t view influencers as paid endorsers or salespeople—even though a significant percentage are—but as trusted experts, friends, and “real” people. This perceived authenticity is part of why brands shell out so much cash in exchange for a brief appearance in your Instagram feed.

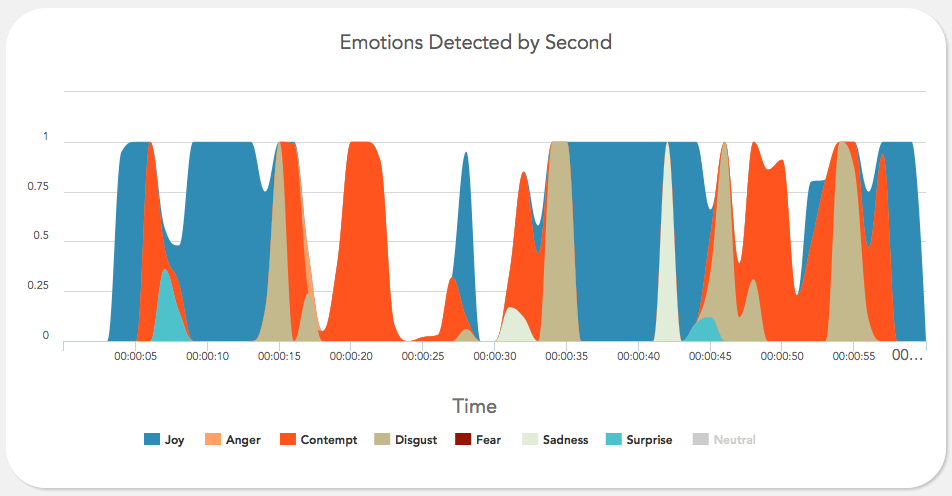

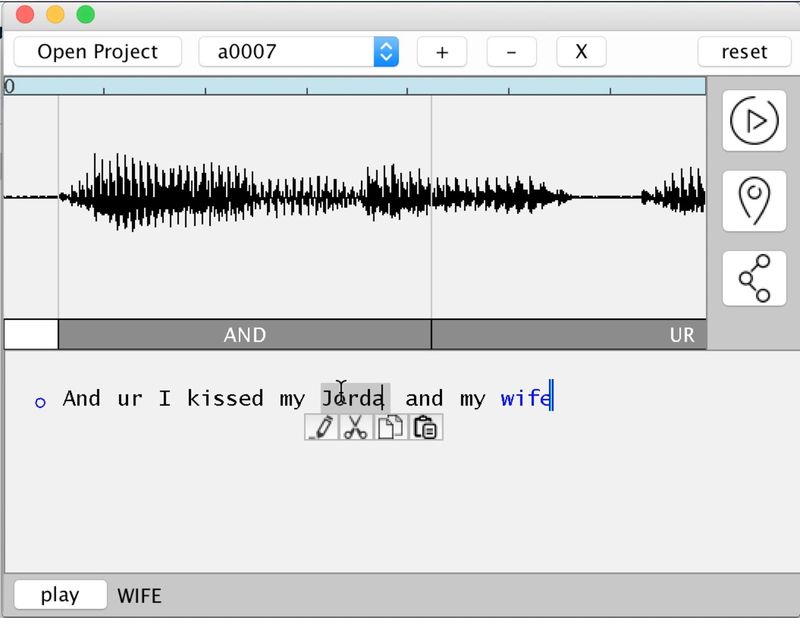

“Right now, in a handful of computing labs scattered across the world, new software is being developed which has the potential to completely change our relationship with technology. Affective computing is about creating technology which recognizes and responds to your emotions. Using webcams, microphones or biometric sensors, the software uses a person’s physical reactions to analyze their emotional state, generating data which can then be used to monitor, mimic or manipulate that person’s emotions.”

“Right now, in a handful of computing labs scattered across the world, new software is being developed which has the potential to completely change our relationship with technology. Affective computing is about creating technology which recognizes and responds to your emotions. Using webcams, microphones or biometric sensors, the software uses a person’s physical reactions to analyze their emotional state, generating data which can then be used to monitor, mimic or manipulate that person’s emotions.”