That Game on Your Phone May Be Tracking What You’re Watching on TV

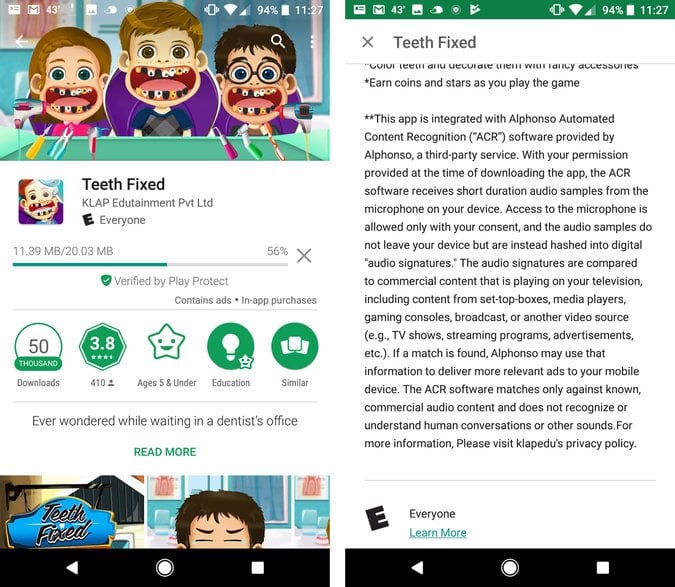

At first glance, the gaming apps — with names like “Pool 3D,” “Beer Pong: Trickshot” and “Real Bowling Strike 10 Pin” — seem innocuous. One called “Honey Quest” features Jumbo, an animated bear.

Yet these apps, once downloaded onto a smartphone, have the ability to keep tabs on the viewing habits of their users — some of whom may be children — even when the games aren’t being played.

It is yet another example of how companies, using devices that many people feel they can’t do without, are documenting how audiences in a rapidly changing entertainment landscape are viewing television and commercials.

The apps use software from Alphonso, a start-up that collects TV-viewing data for advertisers. Using a smartphone’s microphone, Alphonso’s software can detail what people watch by identifying audio signals in TV ads and shows, sometimes even matching that information with the places people visit and the movies they see. The information can then be used to target ads more precisely and to try to analyze things like which ads prompted a person to go to a car dealership.

More than 250 games that use Alphonso software are available in the Google Play store; some are also available in Apple’s app store.

Some of the tracking is taking place through gaming apps that do not otherwise involve a smartphone’s microphone, including some apps that are geared toward children. The software can also detect sounds even when a phone is in a pocket if the apps are running in the background.

Welcome to the age of behavioral addiction—an age in which half of the American population is addicted to at least one behavior. We obsess over our emails, Instagram likes, and Facebook feeds; we binge on TV episodes and YouTube videos; we work longer hours each year; and we spend an average of three hours each day using our smartphones. Half of us would rather suffer a broken bone than a broken phone, and Millennial kids spend so much time in front of screens that they struggle to interact with real, live humans.

Welcome to the age of behavioral addiction—an age in which half of the American population is addicted to at least one behavior. We obsess over our emails, Instagram likes, and Facebook feeds; we binge on TV episodes and YouTube videos; we work longer hours each year; and we spend an average of three hours each day using our smartphones. Half of us would rather suffer a broken bone than a broken phone, and Millennial kids spend so much time in front of screens that they struggle to interact with real, live humans.

“Data-driven policing means aggressive police presence, surveillance, and perceived harassment in those communities. Each data point translates to real human experience, and many times those experiences remain fraught with all-too-human bias, fear, distrust, and racial tension. For those communities, especially poor communities of color, these data-collection efforts cast a dark shadow on the future.”

“Data-driven policing means aggressive police presence, surveillance, and perceived harassment in those communities. Each data point translates to real human experience, and many times those experiences remain fraught with all-too-human bias, fear, distrust, and racial tension. For those communities, especially poor communities of color, these data-collection efforts cast a dark shadow on the future.”