Facebook Really Wants You to Come Back

The social network is getting aggressive with people who don’t log in often, working to keep up its engagement numbers.

It’s been about a year since Rishi Gorantala deleted the Facebook app from his phone, and the company has only gotten more aggressive in its emails to win him back. The social network started out by alerting him every few days about friends that had posted photos or made comments—each time inviting him to click a link and view the activity on Facebook. He rarely did.

Then, about once a week in September, he started to get prompts from a Facebook security customer-service address. “It looks like you’re having trouble logging into Facebook,” the emails would say. “Just click the button below and we’ll log you in. If you weren’t trying to log in, let us know.” He wasn’t trying. But he doesn’t think anybody else was, either.

“The content of mail they send is essentially trying to trick you,” said Gorantala, 35, who lives in Chile. “Like someone tried to access my account so I should go and log in.”

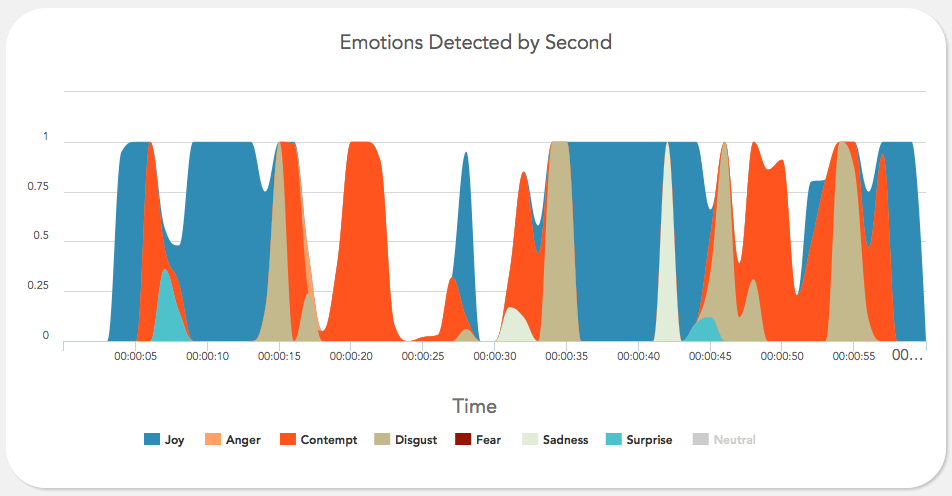

“Right now, in a handful of computing labs scattered across the world, new software is being developed which has the potential to completely change our relationship with technology. Affective computing is about creating technology which recognizes and responds to your emotions. Using webcams, microphones or biometric sensors, the software uses a person’s physical reactions to analyze their emotional state, generating data which can then be used to monitor, mimic or manipulate that person’s emotions.”

“Right now, in a handful of computing labs scattered across the world, new software is being developed which has the potential to completely change our relationship with technology. Affective computing is about creating technology which recognizes and responds to your emotions. Using webcams, microphones or biometric sensors, the software uses a person’s physical reactions to analyze their emotional state, generating data which can then be used to monitor, mimic or manipulate that person’s emotions.”

“An ambitious project to blanket New York and London with ultrafast Wi-Fi via so-called “smart kiosks,” which will replace obsolete public telephones, are the work of a Google-backed startup.

“An ambitious project to blanket New York and London with ultrafast Wi-Fi via so-called “smart kiosks,” which will replace obsolete public telephones, are the work of a Google-backed startup.