Police Are Using Google’s Location Data From ‘Hundreds of Millions’ of Phones

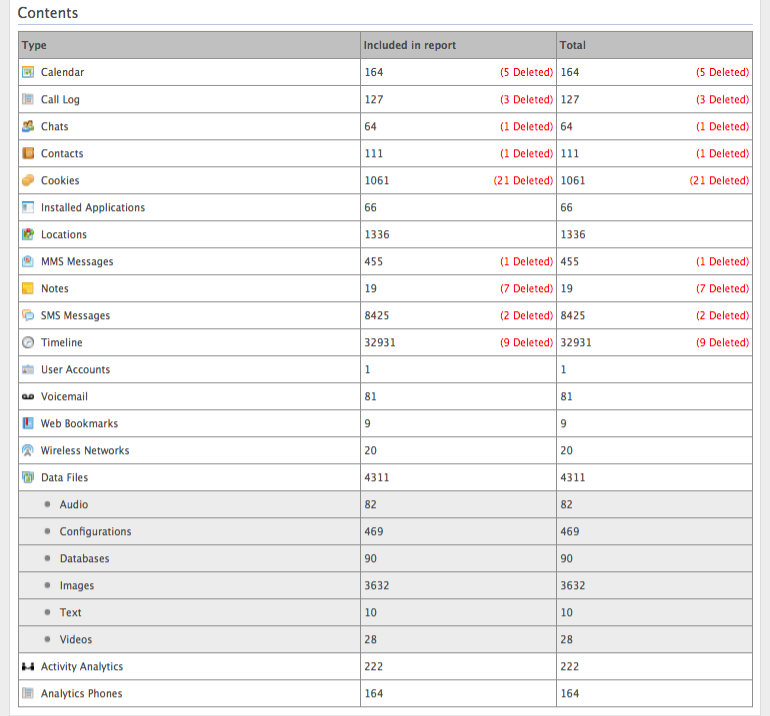

Police have used information from the search giant’s Sensorvault database to aid in criminal cases across the country, according to a report Saturday by The New York Times. The database has detailed location records from hundreds of millions of phones around the world, the report said. It’s meant to collect information on the users of Google’s products so the company can better target them with ads, and see how effective those ads are. But police have been tapping into the database to help find missing pieces in investigations.

Law enforcement can get “geofence” warrants seeking location data. Those kinds of requests have spiked in the last six months, and the company has received as many as 180 requests in one week, according to the report…. For geofence warrants, police carve out a specific area and time period, and Google can gather information from Sensorvault about the devices that were present during that window, according to the report. The information is anonymous, but police can analyze it and narrow it down to a few devices they think might be relevant to the investigation. Then Google reveals those users’ names and other data, according to the Times…

[T]he AP reported last year that Google tracked people’s location even after they’d turned off location-sharing on their phones.Google’s data dates back “nearly a decade,” the Times reports — though in a statement, Google’s director of law enforcement and information security insisted “We vigorously protect the privacy of our users while supporting the important work of law enforcement.” (The Times also interviewed a man who was arrested and jailed for a week last year based partly on Google’s data — before eventually being released after the police found a more likely suspect.)

“Data-driven policing means aggressive police presence, surveillance, and perceived harassment in those communities. Each data point translates to real human experience, and many times those experiences remain fraught with all-too-human bias, fear, distrust, and racial tension. For those communities, especially poor communities of color, these data-collection efforts cast a dark shadow on the future.”

“Data-driven policing means aggressive police presence, surveillance, and perceived harassment in those communities. Each data point translates to real human experience, and many times those experiences remain fraught with all-too-human bias, fear, distrust, and racial tension. For those communities, especially poor communities of color, these data-collection efforts cast a dark shadow on the future.”